Watergate and the Miami connection

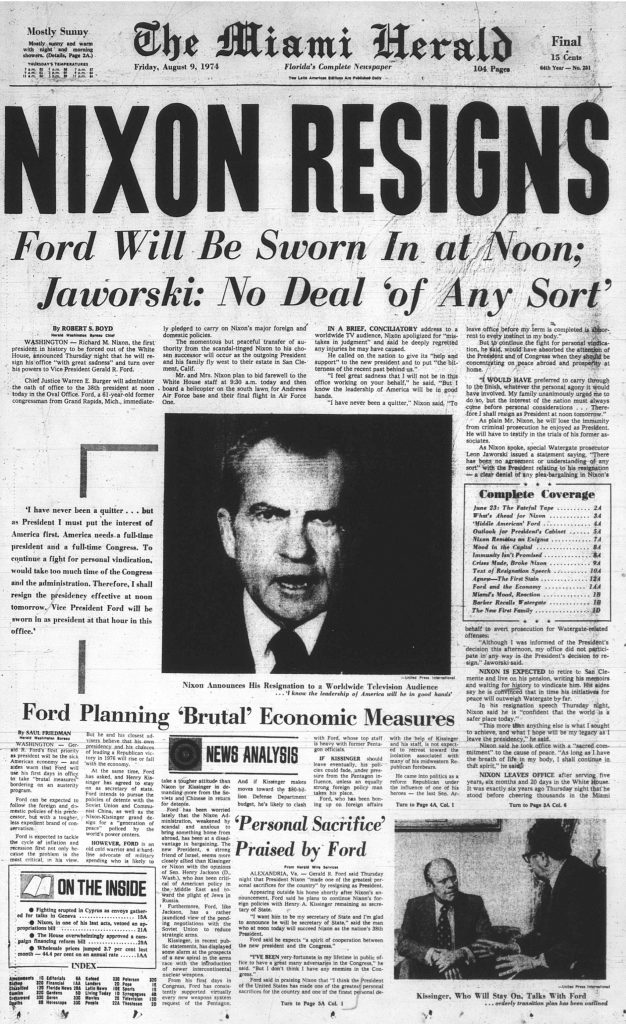

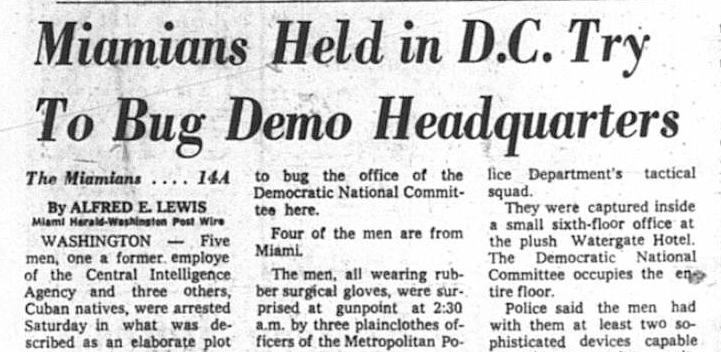

On the night of June 17, five men wearing rubber gloves, their pockets packed with $100 bills collected by President Nixon’s reelection committee, were caught rifling Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate office complex. Four of the five men were from Miami. For the next 783 days, until Nixon resigned on Aug. 9, 1974, one horrifying surprise after another tumbled out of the Pandora’s box that came to be known as Watergate. Secret tapes, blackmail, hush-money, cover-up, obstruction of justice — the list of high crimes and misdemeanors seemed to have no bottom.

BURGLARS’ OTHER GOAL: OUST CASTRO THEIR ZEAL TO FREE CUBA LED TO SCANDAL

By MIRTA OJITO Herald Staff Writer

1992

Stripped of fake ID, surgical gloves and pencil-thin flashlight, Bernard Barker, World War II hero and Bay of Pigs veteran, sat in a cell at the Washington, D.C., police headquarters. It was June 17, 1972, and he was now called a burglar. A Watergate burglar.

He flinched when an FBI agent approached. It was an old acquaintance: “Bernard Barker!! What the hell are you doing here?”

What indeed!

Just a few hours before, Barker and four other men — three of them from Miami — had been arrested at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex. They were wearing suits stuffed with bugging devices and $2,293 for expenses. Most unusual garb for burglars.

They were men with a cause. Three Cuban exiles and an Italian-American who for years had been part of the Cuban fight: Bernard Barker, 55, realtor and broker. Rolando Eugenio Martinez, 49, realtor. Virgilio Gonzalez, 47, locksmith. Frank Sturgis, 47, soldier of fortune.

For them, nothing was ever the same again. Sturgis, now 67: “I was more successful in overthrowing a president of the United States than in overthrowing Fidel Castro.”

They claimed then and now that they didn’t know what they were doing was illegal. They reasoned that if this operation had the blessing of the White House, it wasn’t a burglary. It was, as Barker likes to call it, a “surreptitious entry.”

They had been ordered to photograph all documents; to bug all phones in the office. They had been told by CIA men that Democratic presidential hopeful George McGovern was receiving money from Castro and Ho Chi Minh. And they were looking for proof.

It wasn’t the first time Washington asked for their help.

In September of 1971, Barker, Martinez and another Cuban named Felipe De Diego, led by longtime CIA man Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy, finance counsel to the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), broke into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist looking for information that would help indict Ellsberg for releasing the Pentagon papers.

In May of 1972, the Miamians were again recruited. This time, Barker, Martinez, Gonzalez, Sturgis, De Diego and five other Cubans — among them a book publisher named Reinaldo Pico and a contractor named Hiram Gonzalez — went to Washington to break up an anti-war demonstration on the steps of the Capitol, as the body of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover lay inside.

And, finally, there were the Watergate break-ins. On Memorial Day, after two unsuccessful attempts, Barker, Martinez, Gonzalez, Sturgis and James McCord, security coordinator of CREEP, took pictures and planted wiretaps while De Diego and Pico stood guard outside. A few days later, the bugs needed to be repaired. So they went back. This time, without De Diego and Pico.

“God knows what would have happened if we hadn’t gotten caught,” Barker says. “The things Nixon could have done for Cuba!”

Here are the stories of the Miami men who, propelled by their zeal and those who played upon it, found themselves convicted of betraying the same government that sought their help.

BERNARD BARKER: Bay of Pigs veteran,‘I have no regrets’

“Macho” Barker, as those who know him call him, was born in Havana, of a Cuban mother and an American father. He lived in a northwestern seashore town, Mariel.

At times, Barker says he is an American. Other times, depending on what he is talking about, he says he is ” 100 percent cubano.”

He speaks both languages without the trace of an accent. At 75 and retired, he lives in West Dade with Margarita, his wife of 2 1/2 years.

Margarita was an early love. They fell in love as students in Cuba. But World War II separated them, when Barker, the first Cuban to volunteer for the war, left the island. He spent 16 months as a prisoner of war when his plane was shot down over Germany.

Before Castro came to power, Barker says, he was recruited by the CIA, where he worked for seven years. Then, like thousands of Cubans, he came to Miami. He got a job managing a parking garage.

In 1961, he was one of the Bay of Pigs organizers. That’s when he met Howard Hunt. So, when Hunt asked him for help, Barker thought this time he had found the government support the Cubans had been longing for. Hunt was calling from the White House, where he had an office and a job as a consultant.

“And then he tells me, ‘This would put us in a situation in which we can later ask for help for the freedom of Cuba.’ He was putting himself in our place, as if he were a Cuban,” Barker adds. “To me, Hunt’s words meant that he was making a promise to do everything possible for the freedom of Cuba.

“And when my former CIA boss, my friend, a person I admired, and with whom I am totally in agreement on all major issues, tells me this in his office, in the White House,” Barker stresses these last two words, “and he is an assistant to the president of the United States, you better believe I believed him.”

In jail, where Barker spent 13 months, he decided to go back to school. In 1978, he graduated from FIU with a bachelor’s degree in engineering, the career he had intended to pursue when he left Cuba for the war.

At the same time, Margarita was also finishing her bachelor’s in education. The two met again after 44 years. She was a widow; he was getting a divorce. They married quickly.

This is what Barker thinks of his role in history: “I sleep good at night. I have no regrets. We Cubans, at the time, knelt down and prayed and hoped the government would keep its promises. That’s all we could do then and that’s all we can do now.”

One other thing. Barker really hates to be called a burglar.

EUGENIO MARTINEZ: Says he’s ashamed of his role in scandal

At one point during the Watergate investigation, Sen. Howard Baker asked Martinez what he thought of what was happening to the U.S. government and if he had analyzed the significance of his actions.

“If you don’t know, how am I going to know? I am just a Cuban from Artemisa,” Martinez recalls.

He was born on the outskirts of Havana, in Artemisa, a town he proudly calls “the birthplace of revolutions, of rebels and of civic spirit.”

Martinez had his first lesson in politics during the government of Gerardo Machado, in the early ’30s. The rural police showed up at a political rally in his town and from their horses used machetes on peaceful activists. His neighbor was killed that night.

He fought against Machado. Then, against Fulgencio Batista. And, eventually, against Fidel Castro, whom Martinez and hundreds of other young men and women had helped bring to power in 1959.

That same year, he returned to Cuba from exile in Mexico, but by December, Martinez was one more Cuban exile in Miami.

Martinez is a veteran of many missions to Cuba — getting in and out of the island to foment counterrevolutionary activities was his expertise. He says he never kept count, but during the Watergate years it was revealed he had participated in 354 missions to Cuba from 1960 to 1970, under the auspices of the CIA.

“I still have a hard time saying CIA. I wasn’t recruited by them. I never had an ID. I was recruited by good americanos who wanted to help Cuba.”

Martinez said he wept when John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

The only Watergate burglar to be pardoned later, Martinez works as a manager at Anthony Abraham Chevrolet. At 69 and the grandfather of eight, he is fit and strong. When Castro falls, he insists, he’d be the first to go back to Cuba.

He claims to be deeply ashamed of his role in the scandal. “I wish I could forget about it. I didn’t come to this country to become a criminal and to be judged by the same people to whom I owe all my loyalty.”

Who does he blame for Watergate and his 14 months in prison?

“Fidel. We were doing something for Cuba. If it hadn’t been for Fidel, I wouldn’t have ever been in Watergate.”

VIRGILIO GONZALEZ: Still feels McGovern had ties to Havana

In 1952, Gonzalez was already a political refugee. He arrived in Miami seeking refuge after Gen. Fulgencio Batista’s coup against Carlos Prio, Cuba’s last democratically elected president. Gonzalez was a member of Prio’s secret service.

Like Martinez, Gonzalez also went back in 1959, hoping democracy had returned to Cuba. By April of the same year he was back in Miami, already conspiring against Castro.

He bought a home in northwest Miami, where he still lives, and settled into his job as a locksmith.

Then, one day Barker and Hunt asked him for help opening some doors.

“I always thought that having a Republican government behind us would be great. The Democrats had already betrayed us at Bay of Pigs. So, what better way to get their help than helping them first?” he reasons.

Gonzalez still believes that one day, proof will be found that McGovern had ties with Havana and Hanoi.

Even after he served 14 months in jail for the burglary, Gonzalez continued opening Miami locks and programming downtown bank safes.

He is not ashamed of Watergate. On the contrary: “It gave me personality and friends. I’m part of history. My name is in the books in this country.”

From Watergate, he learned one important lesson: “Nobody who works for a government can expect that government to save him when the time comes.”

Yet, he is proud of this country. His son was in the Army and the National Guard. And, when Castro falls, Gonzalez says he will stay in Miami.

FRANK STURGIS: Has fought communism around the world

With his white guayabera, black hair combed back and gold cross dangling from his neck, few wouldn’t think him Cuban.

In fact, when the burglars were caught in Watergate, they were described as “the Cubans.”

“It could be crazy Cubans,” said Howard Simons, the Washington Post’s then-managing editor, as a reason not to make the burglary the top story in his paper.

But Sturgis was really born in Virginia, to first generation Italian-Americans; his last name was Fiorini. When his mother remarried, he took his stepfather’s name and moved to Florida, where he met some Prio sympathizers.

To spy on Castro for Prio’s men, he says, he joined Castro’s rebel forces in the mountains of Oriente, where he achieved the rank of colonel. When the rebels came down, Sturgis got a job with the new air force.

Soon, he had to escape Cuba and came back to Miami. Because he fought with a foreign, enemy army, he lost his U.S. citizenship but quickly got it back.

Sturgis belongs to a militant anti-Castro group and lives with his wife and 13-year-old daughter in South Dade. At 67, he looks young and fit and admits to coloring his hair jet black.

He keeps an aura of mystery about his activities but is not shy about dropping hints of his latest exploits.

In recent years, he says, he has traveled to Angola and Argentina to fight Communists.

Sturgis says he also met with PLO leader Yasser Arafat two years ago in a secret mission. He has pictures of himself with Che Guevara in the Cuban mountains and with South African intelligence men somewhere in Angola.

“I’m still patriotic and would do anything for my country. But I learned one thing,” he says. “If I ever had to do something for my country again, I’m going to make sure it’s legal. It’s tough. I had never been in prison before.”Sturgis spent 14 1/2 months in prison, where he thought much about Castro: “I kept thinking, Castro couldn’t get to me, and my own country put me behind bars. What an irony!”

HOWARD HUNT:’Plumber’who recruited Miamians

The man who recruited the Cubans and spent 33 months in prison for his role in Watergate, would not talk to The Herald.

“Can you imagine 20 years?” he said when a reporter went to his house in Biscayne Park to interview him.

A career CIA man, he was hired in 1971 by fellow Brown University alumnus Charles Colson, special counsel to President Nixon, as one of the White House “plumbers.”

Before he closed the door to the reporter, he said he had already said everything he was going to say about Watergate.