Paradise Lost –And Regained

Philip Wylie, the famous American author-philosopher came to Miami in 1929, when the town lay in the backwash of bust and the Depression, and rusting steel skeletons of unfinished buildings stood as monuments to community despair. He kept a home here until his death in 1971. And often, he wrote about his adopted city — its struggles to survive the spoilers and polluters, the geography and climate that make it unique — “this place,” he wrote, “where new things constantly happen.” He wrote this article for the second issue of the Miami Herald’s Tropic magazine in 1967. The story predates Time Magazine’s article in 1981 about South Florida — titled “Paradise Lost?” — when the crime rate had gone off the charts. The original, digitized pages of Wylie’s piece are posted below, with the text following. The descriptions of Florida’s natural world and those who would ruin it remain relevant decades later.

October 22, 1967

PARADISE LOST –AND REGAINED

Philip Wylie recalls the dark days

when South Florida poisoned itself,

and warns: “It could happen again”

By Philip Wylie

The boom of 1928 had collapsed, Wall Street’s Black Monday was history and the bread lines began to form. A skinny young writer was told by his doctor he needed to get away from Manhattan to a warm climate for the winter. The Arizona desert say, or South Florida. He’d had too many colds, he needed to rest otherwise he might die of pneumonia or TB.

The boom of 1928 had collapsed, Wall Street’s Black Monday was history and the bread lines began to form. A skinny young writer was told by his doctor he needed to get away from Manhattan to a warm climate for the winter. The Arizona desert say, or South Florida. He’d had too many colds, he needed to rest otherwise he might die of pneumonia or TB.

The favorite recreations of that patient were aquatic. And the desert seemed to offer poor chances for swimming, fishing, boating, what was called fancy diving or, even, any forest where his northwoods skills might be enjoyed. So he took a slow train to Miami.

He arrived on a winter day that was cool for the region. He didn’t know. And before the sun set he had rented a small house on an outlying street of a town called Coral Gables. The next morning while his coffee was brewing he stepped out on his new back porch. The house was still chilly but he found with amazement that the temperature was almost 80 in the yard. And grapefruit were spilling to earth from a nearby tree. He gathered a few, sliced one in halves and for the first time ever he tasted a tree ripened specimen of that fruit. Delicious. And fantastic for the day was in January. I think, since I’m the character just described.

And because I never forgot that first morning I suppose my enthusiasm for South Florida was as instant as it has been enduring. In the following years I returned to the Gables or Miami Beach when I could. But I spent parts of those years in all seasons writing motion pictures in Hollywood. People go to Southern California for winter vacations, too, and did then. but I never could see why they thought the climate was warm. Raw and windy, rainy and clammy, and once I stood in the lot of United Artists while heavy snow fell from a low, mean sky. There was fog, too, though it later became smog.

South Florida in the early 1930s was plainly different. Winter cold spells were rare and short. Most of the time, I found, it had the perfect summer days people enjoy up north. Now and then. But there was a somber thing about Florida, too. The dreams of boomtime developers had died. Miles of paved streets around the Miami area cracked open and grass grew in the crevices. Grass, then weeds and soon, even trees. There were only a hundred and some odd thousand permanent residents in Miami then. Their main industry, winter tourism, had dwindled. After each long, job-scarce summer many kids had that pot-bellied look of undernourishment

Skeletons of steel rusted among the completed tall buildings of downtown Miami. 0n the Beach to the north of the Roney Plaza Hotel and the neighboring Wofford only occasional seafront houses interrupted the tangled vegetation clear to the MacFadden – Deauville. Beyond that there was even less evidence of human habitation. A friend of mine, Capt Dave Curtis, once said he’d had his last successful crocodile hunt in the bayside mangroves of the Beach, in 1933. Not gators –crocs.

I learned, in my first Florida winter, that a northwoodsman however skilled, isn’t equipped to explore the South Florida wilderness. I’d seen some big bass boiling in the canal along the Tamiami Trail. The next day I bought some casting tackle and parked off what then was a little-traveled route. I hurried through the weeds and grass and oolite rock from my car to the bank and began to cast. I didn’t get a bass and couldn’t identify the fish I did catch. But when I gave up and turned to walk back to my car I got my first lesson about this new region. Here and there in the rock-strewn stretch I’d casually

Raw sewage made Biscayne

Bay a cesspool. Miami had the

highest VD rate of any city.

The highest rate for TB, too. It

was tainted by dengue fever.

malaria, typhoid. And kids

who went wading contracted

Florida sores.

crossed I now saw dozens of snakes, cotton-mouth moccasins. I’d been so eager to start fishing I hadn’t even looked, or thought. It took me about 20 anxious minutes to cover a distance I’d made before in 20 seconds.

But soon after that I luckily met a Coral Gables physician, the late Dr. Michael Price DeBoe –a peerless explorer of the Everglades who had what was probably the world’s finest collection of liguus shells, the painted snails of Glades hammocks and the fastnesses of the then-wild Keys. “Bo” DeBoe was the man responsible for the recovery of roseate spoonbills, thought to be extinct when he heard of a colony on a remote isle in the Bay of Florida and told the Audubon people. He undertook my education in this unfamiliar land.

Another friend, that first winter, invited me to go deep sea fishing. I’d fished in brooks and ponds, rivers and lakes ever since the age of eight. For bass, pickerel, pike, muskies. trout, and so on. But when my new friend and I came in that day with 19 kingfish several of which were larger than my best fresh water prize I’d found what would become my principal sport (and eventually a near vocation) in this new tropic region.

It won’t be easy for most people who now live in South Florida to imagine it as it was then. The Everglades weren’t criss-crossed by swamp buggies and air boats. People got lost in the immense mangrove labyrinths and some for good. At almost every edge of inhabited places stood huge arches, entrances to proposed developments that never became more than those gateways. Even in the city there were many houses on once-expensive lots where the jungle had swallowed all but rooftops and pushed into broken windows. Tunnels of trees and vines enclosed paved streets where lamp posts fell, finally, in and vegetation obliterated the shards of concrete sidewalks where no one walked.

The tourist season then was four months long and by the end of April the winter visitors also had departed, leaving hotels,

If too many people cop out as citizens, the

area could become a worse version of

what it once was: a slum in the sun.

apartments and miles of pretty houses boarded up and empty, unlighted at night – ghost towns with lawns grown rank. As America slowly climbed out of its Great Depression, conditions slowly improved in the Miamis. A bold slogan was adopted: “Stay through May”

By then I’d given up movie writing and Southern California was no place to be if you could be elsewhere, especially in Florida. And in 1937 my wife Ricky and I decided to build a home on DiLido lsle off the Venetian Causeway. That and the County Causeway and the Haulover Bridge were the only routes to the beach then.

Ricky and I fished a good deal, perhaps a hundred days in some years. We shared an intense interest in the sea and its cobalt Gulf Stream, the dark drum-resounding nights in the Bahamas, the panther-prowled jungles on the Keys, the fantastic Everglades and its unique flora and fauna, the green-dreaming Ten Thousand Islands and the opal calm mornings on the vast Bay of Florida. Westerners once called and may still call their monotonous prairies or bleak mountains “God’s Country”, but if I were to use the term it would be to mean any place on earth that remained exactly as it had been before man invaded it to farm, raise cattle, hunt or in any other way alter the landscape. There was a great deal of such country in South Florida in those days and some has been preserved. And there was plenty of room for people, too.

We got to know some of the men who’d started the people part of the dream: Newt Roney, George Merrick and Carl Fisher. I felt from my first visit that their visions would be realized, even though they had faltered. And when occasionally, I was asked to address a business group or luncheon club I said as much. In the 1930s I’d get a tremendous laugh, not applause, when I’d predict the Miamis would have a population of a million within a quarter of a century. No Miamian laughs now, even when the imminence of a population twice that is discussed; it’s inevitable.

But as South Florida gradually recovered I found that the paradise was sick. Raw sewage made Biscayne Bay a cesspool. Miami had the highest VD rate of any American city. And the highest rate for TB too. It also was tainted by endemic ills that sometimes became epidemic: break-bone or dengue fever, malaria, typhoid. Kids who waded in the South Florida waters contracted “Florida sores”, staph infections from filth that were difficult to cure.

So, when my wife contracted the also common undulant fever (from which she suffered intermittent agonies for seven years) I got mad not at Florida but at the Floridians who did nothing to change the intolerable circumstances. The more I studied them the more unforgivable they proved. But most folks said that standard urban health measures were not only impossibly costly here but needless. The sun, they insisted, killed all germs and was a sufficient public health agent.

I’d been asked by another new friend, John S. Knight, publisher of The Miami Herald, to write for it now and then. And when I put before him some statistics on the sickness of our cities he had me write them for his paper. So did James Cox and Dan Mahoney at The News. It was the start of a long campaign interrupted by World War II and violently opposed as too costly by many business leaders and countless taxpayers. But it slowly attracted other people and in the end our South Florida megalopolis became a model for the application of medical knowledge to public health and for construction innovation. Architects and engineers from cities in hot countries the world over came here to learn.

I was not a popular person when I kept writing the appalling facts about our polluted paradise. But I used that grim information only in the gutsy local press, save for one occasion when I wrote about part of our mess for a national weekly – to prove that sickly cities, however sunny, would not attract tourists. The national reaction was violent and my point was made.

South Floridians cleaned up the shambles. They are special people. For example, they were first to engage in the Great War. Only months after Pearl Harbor, Nazi subs began to destroy the tanker and cargo ship lifeline that voyaged north in the Gulf Stream and our Defense Department had no weapons to spare for counterattack. So charterboatmen and the owners of sporty speedboats signed up for patrols to try to keep the subs down and to rescue crews of torpedoed vessels, often racing through acres of blazing oil to get to those men. Not all of these volunteers came back. And we weren’t allowed to rouse a then apathetic America by publishing the story of blacked-out, heroic South Florida – not for years, because the facts would have tended to reveal how poorly prepared our brass had been.

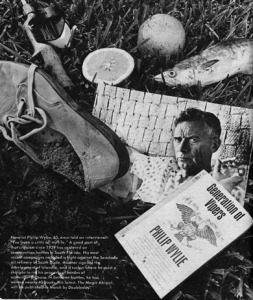

It was anger at post-Pearl Harbor apathy (and at other faults of my fellow citizens) that caused me to write my best-known book, Generation of Vipers, in six weeks in that DiLido Island home. And there I also wrote the first story about deep sea fishing and two imaginary charterboatmen I called Crunch and Des. It was published in The Saturday Evening Post and created a demand for more. In the next 20 years I wrote six bookfulls of those fishing yarns and in them I naturally described what I cherished in my adopted land. The same Miamians who opposed my criticisms of the area before were delighted with that national praise.

Many folks considered it deliberate “publicity”. And after those tales had appeared for a while, newcomers began to tell me that their first fascination for our magic peninsula came from reading about Crunch and Des. The yarns, however, weren’t written as publicity. All that was spin-off, though truth. I wrote for a living and I’m probably one of the few men who have made more money from big game fishing than they’ve spent on that costly sport.

Looking back over nearly 40 years, remembering how it was and what the Miamis accomplished. I often think of the old-timers, long gone now, and I realize I’ve become one. But I don’t know how to be old and I don’t feel old, because, perhaps, so much of my life has been spent in a place where new things constantly happen and where our primeval, green, sunny surroundings don’t cue people in with autumns and winters, the annual old-age symbols in the North.

Besides, I still get into crusades like those fought when I was a newcomer to the Miamis. I recently helped make it clear, for instance, that we don’t want oil-cracking plants and chemical smoke factories in our domain. And I’m plotting against the needless devastation of our hard-won Everglades National Park through engineering idiocy. So, I’m an impassioned conservationist. But not, as some say, because conservationists prefer birds to people. Our motive is in the fact that human existence is dependent on Nature. We want to keep our area, and all areas, habitable and enjoyable for posterity. We know that all people to come will thrive or fail according to how we preserve or win our natural resources; our acts will give our heirs a way of life beyond even dreaming.. .or one they may be unable to bear.

All of this has had its rewards. I remember a commencement night at the University of Miami. It had been a one-building near-calamity when I first saw it. And I’ve helped it grow. I made an address to the graduates and Bowman Ashe, that self-sacrificing man who single-handed started “Cardboard College” toward what it has become, read my citation. Then a leading trustee put the hood of an Honorary Doctor of Letters over my shoulders. Later in the evening that trustee took me aside. He’d been head of a great corporation that had fiercely opposed my long-ago war for public health. Now he took my hand. Tears ran down his cheeks. He could barely talk, but he said: “never in my life hated a man as much as I once hated you. But, by God, Phil Wylie, you’re decent!”

How many men have received such a reward? What word would make a better epitaph?

Our acts: will give our heir

a way of life beyond even

dreaming . . . or one they may be

unable to bear.

The boomtime miracle petered out. But what was gained later, or regained, anybody can see. And if these random recollections of one who played a small, occasional part in making this a better place seem boastful, I am sorry. For they have a different intent. I’m a person who, at least sometimes, practices what he preaches. And this account is meant as a parable.

Paradise can be lost again, any paradise, and easily. Sinners don’t get into heaven, always. And our gaudy South Florida wonderland can be lost by another sort of sin and an invisible specie of sinner.

The great majority of people here have come by choice or perhaps by the choice of their parents. Tens of thousands gave up better jobs, higher salaries, promotions to come here to live. Other myriads have retired and come here because they planned and saved for it all the decades of their working lives. And as our area has grown and prospered, some have gained greatly by that. Still others, the fortunate few like me, can make our livelihood anywhere and chose to do it here. We are, then, mostly immigrants or the sons and daughters of immigrants.

We left our hometowns behind and now we live in South Florida, by choice, through effort, and in preference to anywhere else.

Yet some South Floridians –far, far too many —enjoy, consume and exploit what they came here to possess. They don’t react to local needs as they did when they lived in Duluth, Milwaukee or Hartford. They don’t relearn. Don’t even know the names of trees on their street or birds in those trees. They won’t even vote in many cases. So they are not real citizens but parasites on their chosen paradise.

I can’t understand them. If a firm a man worked for shifted him willy-nilly to a city he either loathed or even disregarded I would comprehend if not condone that. But they chose South Florida! That special act should make them feel eager and ready to take part in the affairs of their community and to learn about its fantastic environs more so than being born in or sent to it or living in it for any lesser reason than zealous desire.

And so, characteristically, I have ended up an effort to express my enthusiasm and delight –with cavil. But, hopefully, it may cause some readers to realize that they may call themselves residents . . . and act like squatters. If too many people, now here or soon to come, cop out as citizens the area could become a vaster and worse version of what, for a sad while, it was: a slum in the sun.

If so, I’ll move away. But can you? Your children? Move? To some then-better paradise? There isn’t any now. And there won’t be so long as we realize that we must all be maintenance men. Or else.

Magic requires magicians. And the most splendid effects require a certain amount of dreaming to envision and a great deal of work and some courage to achieve. And to sustain. All of which should concern you- if the shoe (and the sand in it) fits. The first dreamers have died. Those who do the magic today need the aid of every resident — and a next generation of as creative, practical and knowing residents must follow.

That in effect sums up my feelings as an old-timer. If you can walk about in, or fly over, this unique and limited part of the nation, understanding how rare its qualities are and knowing them, if you realize the delicate balance of Nature on which all that’s of value here depends, and if then you can also take pride in the visible, dramatic progress as one who contributed to that – while you still are concerned when you note threats to nature growth – you need not have read a word of this piece. You’ll have a warm sense of achieved wonder –as well as your own occasional anxiety to lead you to some further endeavor. I’ll be glad for you.

But if this article irritates you by making you feel justly ashamed. I’ll be glad of that, too. For your discomfort will then measure your status, not as a citizen but a squatter, a predator. And even this paradise can be polished off by parasites.